- Home

- David Barbaree

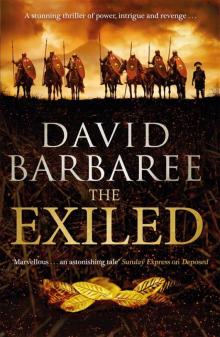

The Exiled

The Exiled Read online

Contents

Cast of Characters

Maps

Prologue

Part I

Zenobia

Gaius

Barlaas

Domitilla

Gaius

Domitilla

Part II

Gaius

Domitilla

Gaius

Domitilla

Gaius

Barlaas

Domitilla

Gaius

Part III

Captain Verecundus

Nero

Part IV

Domitilla

Barlaas

Gaius

Domitilla

Gaius

Domitilla

Gaius

Barlaas

Domitilla

Part V

Gaius

Domitilla

Barlaas

Gaius

Domitilla

Gaius

Domitilla

Barlaas

Domitilla

Gaius

Barlaas

Ten months later . . .

Domitilla

One year earlier

Domitilla

Barlaas

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Cast of Characters

PARTHIA

The Kings of Parthia

King Vologases, ailing ruler of Parthia, king since A.D. 51, sparked civil war naming youngest son, Pocorus II, as his heir

King Vologases II, eldest son of Vologases, one of three sons vying for the throne

King Artabanus III, second son of Vologases, faring badly in the civil war

King Pocorus II, youngest son and heir of Vologases

Loyal to King Artabanus III

Zenobia, wife of King Artabanus III

Darius, satrap of Bactria, advisor to King Artabanus III

Meherdates, aka the Toad, Latinized son of Parthian hostage in Rome, ears shorn off by King Gotarez (aka the Butcher), after failed coup

Himerus, Chief Eunuch of the King’s Harem

ITALY

The Flavians

Vespasian, deceased, emperor of Rome, ruled from A.D. 69–79

Titus Caesar, eldest son of Vespasian, former soldier and general, named emperor after his father’s death in June A.D. 79

Domitian, second born son of Vespasian

Domitilla, eldest daughter of Vespasian

Vespasia, second born daughter of Vespasian

Imperial staff and courtiers

Ptolemy, slave and Imperial secretary to Titus

Jacasta, loyal and long serving maid to Domitilla

Livia, maid to Domitilla

The house of Secundus

Plinius Secundus, aka Pliny the Elder, admiral of the Imperial fleet, soldier, author and close advisor to emperors Vespasian and Titus

Gaius Caecilius, shy, bookish nephew to Pliny

Spartacus, secretary to admiral Pliny

Zosimus, slave to Gaius

The house of Ulpius

Lucius Ulpius Traianus, blind wealthy senator from Spain

Marcus Ulpius Traianus, nephew to Lucius Ulpius

Theseus, one-eyed freedman and former gladiator

Cyrus, freedman to Ulpius

Elsie, elderly slave, like a mother to Marcus

Senators and patricians

Cocceius Nerva, senator fallen out of favour with the Flavians, has network of spies throughout the empire

Sulpicius Peticus, recently returned from Syria, owner of gladiators, brother was put to death under Nero

Cerialis, general and friend of the emperor Titus, engaged to Domitilla

Tascius Pomponianus, lives near Stabiae on the Bay of Naples

Eprius Marcellus, deceased, senator under Nero and Vespasian, conspired to kill and overthrow Vespasian

Caecina Alienus, deceased, former commander during the civil wars, implicated in Marcellus’s conspiracy to overthrow Vespasian

Valerius Festus, arrogant member of Domitian’s entourage

Soldiers and Praetorian Guard

Virgilius, recently named Prefect of the Praetorian Guard and Titus’s right-hand man

Manlius, centurion charged with watching Parthian hostages, Barlaas and Sinnaces

Catullus Messallinus, legate in the Praetorian Guard and good friend of Domitian’s

Parthian hostages

Carenes, deceased, general and satrap of Mesopotamia, supported Meherdates in failed coup to overthrow King Gotarez

Barlaas, warrior of royal descent, co-conspirator with Carenes in the coup to overthrow King Gotarez

Sinnaces, son of Carenes, born in Italy

Parthian emissaries

Arshak, leader of Parthian emissaries, short with miscoloured eyes

Farbod and Farhad, brothers, tall and noble in appearance

Atropates, old translator who wears a Scythian cap

Gladiators and hunters

The Batavian, legend of the hunts, owned by Nerva

Minnow, gladiator, Myrmillo class, owned by Sulpicius Peticus

The Spear of Sogdia, warrior brought by Parthian emissaries to Italy

Locals in Reate

Plinius Pinarius, undertaker, seeking an audience with Domitilla in Baiae

Sextus Pinarius, son of Plinius Pinarius, expected to take over family business

SYRIA

House of Ulpius

Nero, deposed emperor, posing as Spaniard Lucius Ulpius Traianus

Marcus, former slave, now posing as nephew of Ulpius

Theseus (aka Spiculus), former favourite gladiator of Nero

Doryphorus (aka Cyrus), former freedman of Nero, actor and master of disguises

Local patricians

Commodus, governor of Syria

Sulpicius Peticus, senator from Rome, owner of gladiators, brother put to death under Nero

Prologue

The general arrives in the afternoon. Half the city is there to greet him.

‘Shall we begin?’ he asks.

The question is rhetorical: the general sets the agenda, not the other way around. But the priest – a local man, and ignorant of the Imperial protocol – lacks the deference one is expected to show the second most important man in the empire.

‘We must wait,’ the priest says bluntly, ‘until the sun has begun its descent.’

The general grumbles. ‘Wait?’ But the priest is merely a proxy, charged with conveying Apollo’s will. Who is the general to argue?

So, he makes camp. He waits.

Caesar would have come himself. But Caesar is not well; he hasn’t been for some time. Bedridden, rumour has it, never to rise again. The senate decided to send his son, the famous general. After all they collectively thought but didn’t dare say aloud, it’s only a matter of time before the son is named emperor, once Caesar has breathed his last.

At the anointed hour, the general walks through a forest of ancient pines, up a steep hillside, to the Temple of Apollo. The building is more than a thousand years old – older than Rome itself. North African marble façade, grooved columns, and two podiums, separated by a flight of stairs; a hearth burns on the first, day and night. Nearby is a cliff overlooking the Tyrrhenian. The island of Ischia lies in the distance, a shadowy black peak, rising from the sea.

By torch light, the general sacrifices three black bulls and an ox. The animals’ necks are slit and a sea of blood pours onto the dirt; puddles form, gelatinous and black. Acolytes recite ancient verse while the priest, on his knees, with blood-stained forearms, from finger tips to elbows, removes and inspects the beasts’ entrails, running his thumb

along each liver, like a seamstress confirming every stitch. Once certain there are no anomalies, he takes the general through the forest, down a narrow dirt path, to the entrance of a cave.

The general’s companion, a white-haired soldier, is told he must wait with the acolytes.

The priest ducks into the cave; the general follows.

The passage is narrow and dark. The priest leads him into a small room. Torch light slowly illuminates the room and a human size heap in the corner begins to move.

The Sibyl.

She sits up, leaning her back against the rugged wall of the cave.

The priestess is tiny, all bones and sinew, with filthy black hair. She is only a girl, eight or so. But with her pale skin and black eyes, she has the look of an old woman, with one foot in the grave.

‘Speak and she will answer,’ the priest says.

The general hesitates.

As a soldier, he never hesitated. He smiles and thinks, What’s wrong with you? Is this little priestess of Apollo more fearsome than a German horde or a Sicarii assassin? Remember: this isn’t for you. It’s for the priests back in Rome, and the god-fearing Senate. Ask the questions you came here to ask and then go do something productive.

The general clears his throat. ‘The Oracles tell of a calamity for Rome if the last of the Trojans crosses the Euphrates.’ He cannot bring himself to say the man’s name. It would give the imposter too much credence. ‘We have heard rumours of someone claiming to be such a man amassing an army in the east. He could cross the river any day. He may have already. Tell me what I must do, for the good of Rome.’

The Sibyl’s voice is an empty whisper. ‘Fear not. Every empire must fall.’

‘Tell me, priestess’ – the general’s voice is louder as he grows more confident – ‘what must I do to protect the Principate and to prevent war?’

The priestess’s head tips back, her eyes begin to oscillate, as though she is watching the erratic flight of a bee, and her voice becomes as deep as a man’s. She says:

‘When the last of the Trojans is west and east, mountains will fall and black ash will fill the sky.

When the seed of Aeneas crosses the Euphrates, the heart of the wolf will burn, and a plague will take root.

Beware of a mother’s curse. It follows the guilty, even through death.

Beware of the curse of Remus. You are no Romulus.

Beware of Strength. He is your greatest weakness.

When the golden-haired children are gone, a slave shall rule.

Apollo keeps his word.’

She falls to the floor and retches black bile, then curls up into the heap they found her in.

The general is pale when he exits the temple, though later he will claim it was the moonlight, not colour draining from his face – not a sign of fear. He retires to his tent with his grey-haired companion. They drink wine until morning. They talk of war, of women – anything to distract from the oracular bag of bones that the general spoke to.

The white-haired soldier thinks: this was supposed to be a function of tradition, to appease the empire’s superstitious soul. Has it become something more?

Finally, he asks, ‘what did the Sibyl say?’

The general recites what he can from memory. When he’s done, he forces himself to laugh. He is, after all, the great general who ended the siege of Jerusalem. What does he care for the predictions of an eight-year-old girl?

‘Mountains will fall,’ he says to his friend. ‘As though the gods could topple mountains.’

I

Tremors

A.D. 79

Zenobia

1 April

The harem of Artabanus IV, Parthia

The message comes after sunset. The king’s eunuch, Himerus, delivers it. There will be no battle, he says. Not tonight.

Collectively, eighty-eight women – on edge since the foreign army was first spotted this morning – breathe a sigh of relief. Beside me, the queen, who is eight months pregnant, begins to sob tears of joy. The harem is not ready for another fight. The scars of Persepolis – the lives lost and the brutal, long march north that followed – have yet to heal.

The news comes as a surprise, but I don’t share their sentiment. I feel – disappointed. Yes, tonight there will be no battle. But we are at war. The battles will come. A fight, at least, could have ended our exile; a fight could have led to a proper roof over our heads, rather than the smoke-stained canvas I stare at every evening as I wait for sleep.

Himerus concludes the speech with platitudes for our king, reminding us of his unparalleled intellect, his magnanimity, the righteousness of his cause. The flattery is so over-the-top, so ornate, that I nearly laugh. And yet, for some, it appears effective. A few women nod their head in agreement; others mutter prayers for their king. Perhaps only those who have never met Artabanus and have no measure of his character – although I can’t say for certain. I do not, as others do, keep a running tally of those who’ve been granted the honour of sharing his royal bed. There was a time when I kept score, when I was young and competitive and vain. Those days are behind me now, the victories as well.

Once he’s finished, Himerus catches my eye and makes his way across the tent. Some women, anxious for more information or words of encouragement, step into his path or pull at his robes. The eunuch grants a soothing word or a sympathetic sigh, but never once breaks his stride.

When he reaches me, he whispers, ‘The satrap would like a word.’

‘Would he?’ I raise an eyebrow. Is that allowed?

‘He says it is of great importance.’ Himerus’s voice oozes with propriety. He is the Chief Eunuch of the King’s Harem and would never suggest anything that lacked the proper decorum. ‘I will chaperone.’

I nod, fasten my veil and discreetly follow the eunuch outside. Together we march across the camp, a sliver of white moon overhead, and into a different tent – one that’s smaller than the harem’s long, multi-peaked residence. Inside, it stinks of roasted game – ostrich perhaps – and the hint of incense, recently lit; an unsuccessful attempt to mask the smell of cooked flesh that I detest. It is a gesture – a gesture by an intractable old warrior who rarely makes them.

He misses me.

Or he needs me.

The tent flap opens and Darius, the satrap of Bactria, steps inside.

His frame is unchanged since our wedding night: short but powerful, the shoulders of a bull. His smile is the same as well: crooked, exposing a thin line of teeth, full of mischief or menace, depending on where you stand with him. Only his beard is different. It was black once; now it’s mostly grey.

‘Zenobia,’ he says. ‘My loving wife.’

‘I am not your wife,’ I say.

Darius stares at Himerus and twirls his finger. The eunuch obediently spins on the spot, turning his back to us. Save the king, the satrap is the only man Himerus would obey like that.

‘Are you not?’ Darius feigns surprise. ‘Strange, I recall our wedding very well, even after all these years.’

He steps toward me and boldly lifts my veil.

His smile softens. The change is genuine, I think, a sign of affection – though I’m not sure what he sees. I’m past my prime, wrinkled, with a touch of grey. I’m not an old woman – I wouldn’t go that far. But I am no longer the young beauty he married.

‘No,’ I say, ‘I am not your wife. Not anymore. You cast me aside.’

He takes my hands in his and pulls them up to his chest. ‘Never.’

He did. He tossed me out like used bath water, his wife of twenty-four years. I may have failed to give him a child – at least one that survived beyond pregnancy or the precarious first years of life. But I was otherwise loyal, respectful, loving, a confidant, a voice of reason – everything one could ask for in a wife.

In a time of peace, at least.

Then the war came and everything changed. After Vologases, the king of kings, became ill and nearly died, he named Pacorus his successor, the you

ngest of his thirty-eight sons. When two of his thirty-seven brothers refused to accept their father’s decision, this brutal war began. Nobles across the empire were forced to choose a side. Darius chose Artabanus. Then, to find favour with his new king, Darius gave away three of his daughters and me, his favourite wife. It was a good plan at first. I quickly became indispensable in the harem, adopting the role of matron, instructing the king’s young and inexperienced wives and concubines in the complexities of harem life – on its politics and etiquette, on one’s personal toilette, on the art of pleasing their notoriously difficult to please husband. But Darius may have miscalculated: in the race for the throne, my former husband – the distinguished general, the brilliant tactician – may have picked the wrong horse.

‘Do you regret it?’ I ask.

‘Every day.’

‘And what will happen if our king loses? It will all be for nothing.’

‘He cannot lose. I am advising him.’

‘You may have forgotten, my dear, but I am not stupid. Persepolis was a terrible blow. And now we are forced to hide in the forests like animals, as Pacorus, the boy you didn’t think would last a day, holds the west.’

Darius shakes his head. ‘It’s not the boy who impresses. It’s the treasonous men who support him. They have proven more formidable than I anticipated.’

‘But we can agree the war is not going well.’

Darius grins. ‘You see! This is what I miss. Your fire. All my wives are so dull.’

‘Slow-witted is what you mean. And so are you for giving me up.’

Darius sighs and dramatically drops my hands; he paces.

‘Yes,’ he says, ‘that may be true. I gave you up, and that makes me a fool. But there is no going back, is there?’

‘Then why, my dear, have you brought me here?’

Darius broods for a moment, staring at the tent wall. He says, ‘It’s the men who came tonight. The foreigners. What have you heard?’

‘Silly things. We do not get the truth in the harem, only exaggerations the eunuchs and maids tell us.’

Darius shakes his head and says, more to himself than to me, ‘Maybe not so silly.’

‘Are they Roman?’ I ask. ‘We heard they are Roman soldiers.’

The Exiled

The Exiled